The 'Untranslatables' of Digital Aid

What gets lost in translation when digitising?

Digitising aid involves reducing the place of humans in humanitarian decision-making and aid delivery. This means that decisions can be made with organisational systems and algorithms. In November 2024, Mercy Corps, a global NGO, launched a ‘AI Methods Matcher’, a generative AI tool destined to support aid workers making decisions in crisis contexts. Business Insider reported on the news and Alicia Morrison; Mercy Corps’ director of data science promotes “Making that tool available to the people doing the work helps them learn from what has been done and imagine new possibilities”.

This platform was born from a collaboration between Mercy Corps and Cloudfera. Using Nvidia ‘Agentic AI’ technology. The way it works is that it retrieves information from successful past projects and recommends ways forward. According to their website “Agentic AI ingest vast amounts of data from multiple data sources to analyze challenges, develop strategies and complete tasks independently”.

“Now, decisions that aid workers make on the ground – from calculating vegetation health to tracking fertilizer distribution – can be guided by data” (Price. A for Business Insider, 2025)

AI Methods Matcher tracks conversation history and has the possibility to adapt depending on information input later. After being severely impacted by the USAID cuts in January 2025, Alicia Morrison assured to BI that AI development remains a “priority investment area”. Cloudfera reported that developing AI Methods Matcher should soon involve social media and data analysis to feed the system and get evermore efficient responses.

This innovation is symptomatic of increasing the place of technology in aid to increase efficiency in contexts of crises. Through this discussion, I explore the losses in meaning that happen through the process of digitisation.

When you reduce the place of the human in the humanitarian, what gets lost?

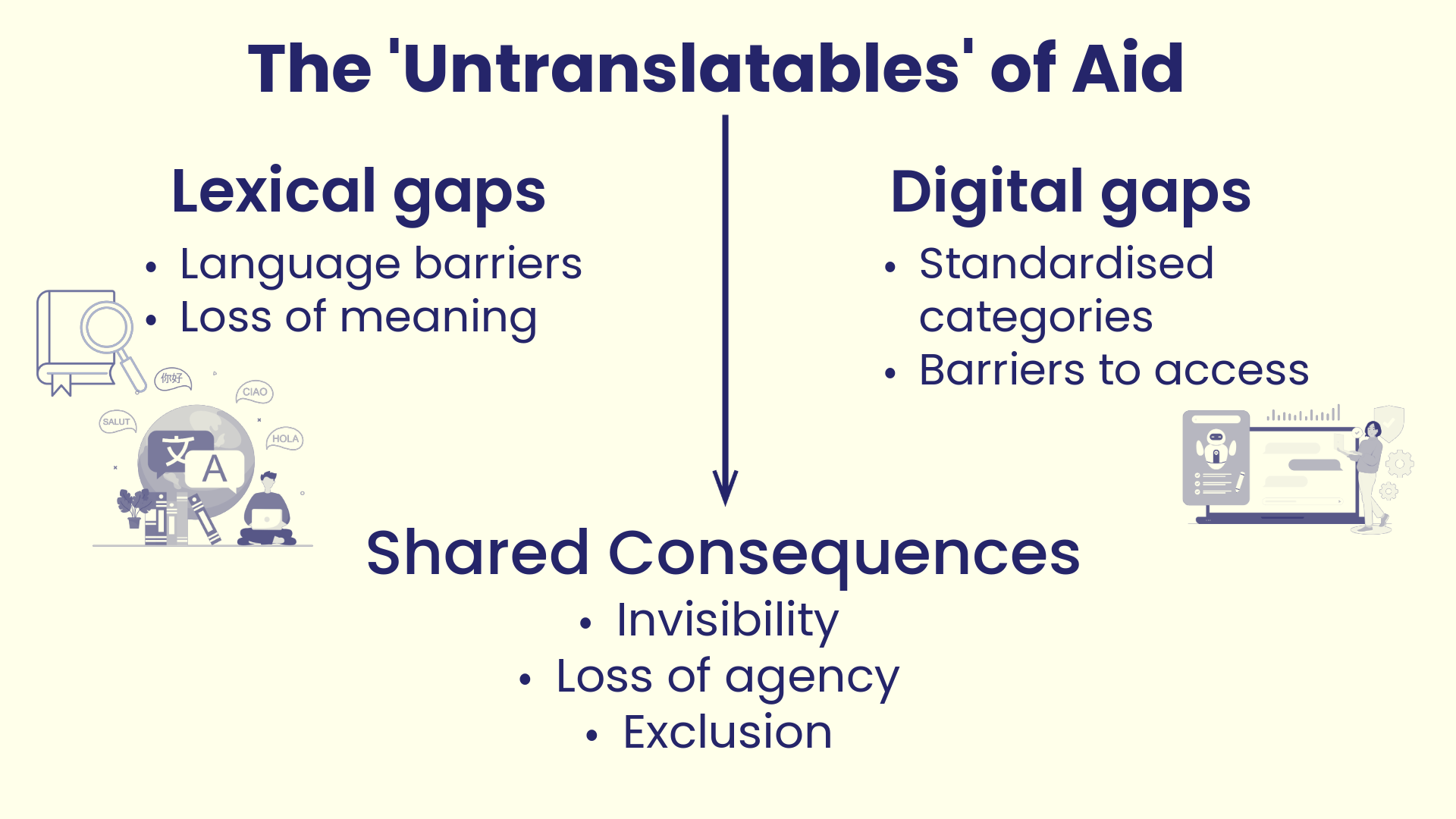

The way technology digests information is through a double process of standardisation and categorisation. In digital aid, complex socioeconomic-environmental context with complex human needs is fed into technologies that require a simplification into a language it can understand. However, when humans step away from overseeing this process: gathering and analysing data to then deliver an organisation response, some things get lost in translation: local expertise, understanding, meaningful and trustful consent, inclusion.

These are the things that get lost in the process of digitisation. I call them the ‘Untranslatables’ of Digital Aid.

Theoretical background

Building on the work of Catford (1965) and Lyons (1977) in linguistics and semantics, untranslatability refers to the phenomenon encompassing a word or phrase that has no direct equivalent in another language. This usually lies in cultural, conceptual and structural differences between linguistic systems. Lyons defines the lexical gap as “a situation where a word or expression exists in one language for a concept that has no single-word equivalent in the target language for a source language item.” 1977 Semantics. Volume 1. (NB: we respectively call source and target language the language that is being translated and the language of translation.)

More recently, in 2011, David Bellos, a renowned translator and scholar of translation studies, nuanced that an untranslatable are not necessarily impossible to translate, but require “explanation instead of substitution” Is that a fish in your ear? Translation and the meaning of everything.

This theoretical background highlights that there are gaps between languages, and they do not and cannot always align. This concept relates closely to semantic fields, which highlight how different languages organise meaning differently, leading to distortion, transformation and inevitable loss. What it also shows is that, when we try and make sense of a concept or phrase that does not have direct equivalents in another language, it takes time and skills in this target language to explain the nuances and carry the meaning.

Why am I talking about linguistics in the context of digital aid? Because language is that the core of aid, it is the medium through which participants talk to humanitarians, it is also what gets inputted into technology to process. It starts and it ends with words.

Language and Aid:

“In disasters […], language barriers can be a matter of life and death” (Uekusa, 2019)

In the context of international aid, language takes a central place. The default language of aid is English, which can hinder the inclusion of local languages and cultures. Historical analysis of Oxfam GB by historian Hilary Footit, reveal that the institution operated under the assumption that English is the language of modernity and progress. Over a century of aid operation led in English have installed it as the language of aid, often at the expense of local languages and systems of knowledge. The use of the English language has been connected to the will to standardise international practices.

“The use of English in international aid organisations such as Oxfam BG has often been framed as synonymous with modernity, professionalisation, and global communication. Yet this linguistic positioning can obscure local knowledges and marginalise non-English-speaking voices in the aid process.” Footit, H. 2017. “International aid and development: hearing multilingualism, learning from intercultural encounters in the history of Oxfam GB” p.519.

Elrha (Enhancing Learning and Research for Humanitarian Assistance) a UK-based charity that seeks to improve humanitarian outcomes through research and innovation. In 2017, they published work on language as a factor of exclusion in humanitarian response, exploring language barriers as contributing to “compounded marginalization”: impeding access to education, legal rights, and essential services. Later, in 2019, Shinya Uekusa, a disaster sociologist and migration scholar, introduces the concept of “disaster linguicism”. He refers to the ideology and practices that discriminates based on language in the context of disaster. For instance, he explored how in Japan and New Zealand non-native speakers struggled to access critical information and services during emergencies, leading to increased stress and delayed recovery. Therefore, language and the failure to propose multilingual and inclusive aid can exacerbate the challenges and risks faced by already vulnerable populations.

Lexical and Digital Gaps: layers of inaccessibility?

The challenge of untranslatability and “lexical gaps” in humanitarian action goes beyond spoken language. It becomes exacerbated and more consequential in digital aid, for we layer inequalities and inaccessibility of linguistic and digital skills. In this context w might think of a digital language gap as the absence of adequate representation of complex, situated situations of crises and needs with machine-readable systems. It takes time and explanation to communicate cultural nuances and digital systems, which are made to fit values into predefined categories, do not account to process local knowledge and emotions.

In other words, the addition of a digital translation to the pre-existing linguistic translation adds a layer of loss of meaning. As aid undergo digitisation, the reliance on standardised categories, datasets and algorithms introduces further gaps – not just of meaning, but of access and representation.

Experiencing ‘Untranslatables’: Insights from Malawi

A note on methodology and ethics

This piece draws on qualitative research conducted during two field visits to Malawi in 2023 and 2024. I used semi-structured interviews with aid workers, educators, and humanitarian practitioners, supported by a local research assistant and translator where needed. The aim was to explore how digital technologies are experienced and understood in everyday humanitarian contexts.

The interviews I led in Malawi with aid workers were conducted in English, with the support of a research assistant and translator for anyone who preferred speaking in Chichewa. Informed consent was obtained in all interviews and the data they provided was analysed according to their preferences.

How are the untranslatables of aid shaping practices?

These experiences offered insight into how digital systems take shape on the ground — not just through technology, but through people’s everyday negotiations with infrastructure, language, and expectation. What follows are moments where the limits of translation become visible, starting with the digital tools used in school-based aid.

Infrastructure and the Digital Divide

In a rural Malawian school participating in a WFP and French government-supported feeding programme, the school director explained that they were given smartphones and trained to use them to report on the results and ask for new deliveries when stock runs low. The headmaster reported feeling “empowered” and “confident” in this technology, although they admitted that they did not know who received the information, or how it was used. This example illustrates multiple levels of translation: from the headmaster’s native language Chichewa to English, from material experience to text and from the human report to the algorithmic analysis. This highlights not only how present the process of translation is in digital aid, but also a great gap in the transparency of digital systems.

The headmaster reported needing to walk long distances to get to a village with electricity to charge the smartphone. Sometimes in their account, the electricity is cut for a while due to disruptions linked to flooding. Ultimately, when asked if they thought continued support from international organisations or stronger community-led solutions would allow for more sustainability in the future, he expressed how much he values the food programme for enabling learners to attend school but also expresses a wish for stronger communities that could one day support the institution independently. They recognised that, while this system increases dependency to international institutions - linguistic, technological, and infrastructural – and stress due to navigating the inaccessibility to a reliable electrical network, local communities were too vulnerable to become independent soon. This dependency to digital aid is due, in their opinion to repeated climatic events, the destruction of agricultural systems and the poverty in the area.

This instance illustrates that beyond linguistic complexity, there are parts of digital aid that are left unspoken – or untranslatable – in current systems. The headmaster’s experience brings a series of infrastructural and emotional challenges: the need to walk hours to charge a phone in the absence of reliable electricity; the stress of ensuring the device is functional to report critical data; the lingering uncertainty about what happens to the data once shared, and who has access to it. These lived experiences are not captured in digital reporting systems that structure aid delivery.

The Limits of Inclusion

A parallel perspective comes from staff at the African Drone and Data Academy (ADDA) who described how participatory mapping was led in communities. This practice has the aim of promoting local experience and knowledge. Maps are then digitised and translated into digital formats for processing and sharing to partners. They are layered with drone imagery. The participant highlights “We compare what they draw with what the drone maps show, so we can highlight what’s really affected”. In this phasing, what is highlighted is that empirical knowledge is analysed with drone data to account for the unreliability of either.

The ADDA’s action takes three main routes: community engagement, emergency response and education. The academy offers training in drone and data science that helps students prepare for the drone licensing in Malawi. Challenges linked to linguistic and digital gaps appear in all these areas of action. Staff reported that students, particularly those with limited educational background with limited understanding of English, felt overwhelmed by the pace and intensity of training, and eventually disengaged: “Some of them, when it gets too much, they just go ‘let me just wait for the programme to end and just go home’.” The gap here is not one of will or interest, but one of coherence and translation – between the assumptions embedded in the curriculum design and the lived realities of learners. The pressure, felt digital gaps in skills, felt lexical gaps in communicating and evolving in an English-speaking environment, all contribute to a degradation in accessibility of this system. The ADDA’s staff is currently developing a curriculum in Chichewa, to become more inclusive of Malawian native-Chichewa-speakers (which is the main mother tongue in the country).

Lived Realities of the Untranslatable

Together, these accounts show that the 'untranslatables' of digital aid are not just abstract values. They are infrastructures, emotions and forms of local knowledge that resist digital categorisation. They exist in gaps between the spoken and the coded, the mapped and the lived, the empowerment and overwhelming.

Making Space for Digital ‘Untranslatables’

This reflection shows that the ‘untranslatables’ of digital aid are not just theoretical shortcomings, they are limits of the digitisation process.

For those working on the frontlines of humanitarian response, navigating the gaps and ‘untranslatables’ is a constant reality, adding to the pressure of leading work on the ground for aid workers. From practical challenges with school directors navigating unreliable digital infrastructure to students struggling through technical training programmes, the friction of translation: cultural, linguistic and digital, accumulates. These are structural challenges that do not reflect individual shortcomings but systems that lack fitness to the needs they need to account for. In other words, digital aid systems struggle to accommodate the full complexity of human experiences.

What gets lost in translation isn’t just language—it’s agency, context, and emotional nuance. As aid undergoes this process of digitisation, the gaps between the empirical and the digital grow. Therefore, digital aid needs to be approached critically by humanitarian organisations, accounting for what resists translation and challenging whose voices are heard in digital design.

As highlighted earlier, one of the key tools to accommodate ‘untranslatability’ is explanation rather than substistution (Bellos, 2011). In the context of aid, this extra step of time and effort can be unrealistic for situations of emergency or accounting for the efforts provided by aid workers on the ground.

Making space for local knowledge, linguistic diversity and cultural contexts is an essential step to improve humanitarian technologies’ accessibility, inclusivity and eventually, sustainability. A sustainable and inclusive digitisation of aid means creating spaces online for new voices to be encoded and embracing a long-term development process of adapting current systems to account for complex realities.

Keep exploring:

Quoted here:

- Bellos, D. (2011). Is That a Fish in Your Ear? Translation and the Meaning of Everything. Penguin.

- Catford, J.C. (1965). A Linguistic Theory of Translation. Oxford University Press.

- Elrha. (2017). Language Matters: Lessons on language in humanitarian response. [online] Available at: https://www.elrha.org/researchdatabase/language-matters/

- Footitt, H. (2017). ‘International aid and development: hearing multilingualism, learning from intercultural encounters in the history of Oxfam GB’. In: Delabastita, D. and Grutman, R. (eds.) Fictionalising Translation and Multilingualism. Translation Studies Series. John Benjamins, pp. 505–524.

- Lyons, J. (1977). Semantics. Volume 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Price, A. (2025) A humanitarian organization is using generative AI to help workers in the field make better decisions. Business Insider. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/mercy-corps-generative-ai-tool-humanitarian-aid-workers-field-information-2025-6 (Accessed: 5 June 2025).

- Uekusa, S. (2019). ‘Disaster linguicism’: Linguistic minorities in disasters. Language & Communication, 66, pp. 1–11